Oncoscience

Abstract | PDF | Full Text | Supplementary Materials | How to Cite | Press Release

https://doi.org/10.18632/oncoscience.637

Incidence and risk factors for new-onset diabetes mellitus (NODM) in post-pancreatectomy patients diagnosed with pancreatic adenocarcinoma (PAC): A systematic review

Adavikolanu Kesava Ramgopal1, Chandramouli Ramalingam2, Kaliyath Soorej Balan1, K.S. Abhishek Raghava3, Kondapuram Manish2, Kari NagaSai Divya2, Yadala Ambedkar4, Varthya Shobhan Babu5 and Kondeti Ajay Kumar2

1Department of Radiation Oncology, All India Institute of Medical Sciences (AIIMS), Mangalagiri, India

2Department of Radiation Oncology, AIIMS, Bibinagar, Hyderabad, India

3Department of Medical Oncology, AIIMS, Mangalagiri, India

4Department of Radiation Oncology, JIPMER, Pondicherry, India

5Department of Pharmacology, AIIMS, Jodhpur, India

Correspondence to: Kondeti Ajay Kumar, email: ajay.radonc@aiimsbibinagar.edu.in

Keywords: pancreatectomy; pancreatic adenocarcinoma; diabetes mellitus

Received: September 02, 2025

Accepted: November 26, 2025

Published: December 8, 2025

Copyright: © 2025 Ramgopal et al. This is an open access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (CC BY 4.0), which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original author and source are credited.

ABSTRACT

Background: Pancreatic adenocarcinoma is a highly aggressive malignancy often requiring pancreatectomy as part of curative treatment. However, pancreatectomy frequently leads to endocrine dysfunction, such as new-onset diabetes mellitus (NODM). But the relationship between post pancreatectomy NODM and pancreatic carcinoma and the relevant risk factors remains underexplored.

Methods: In accordance with the PRISMA guidelines, a systematic search for pertinent studies was conducted across electronic databases including MEDLINE, Cochrane, EMBASE, and Scopus, covering the period from January 2000 to March 2025. The quality of these studies was evaluated using the Newcastle-Ottawa Scale, specifically designed for cohort studies. Subgroup analysis was done in terms of different pancreatectomy procedures.

Results: 45 quantitative studies were analysed, of which 16 (35.5%) were prospective studies and 29 (64.5%) were retrospective studies. Regarding the subgroup analysis, 11 studies analysed Pancreatico-Duodenectomy (PD) alone, another 12 studies analysed Distal Pancreatectomy (DP) alone, and the rest of the 22 studies compared PD with DP. The overall incidence of NODM was 24.5%, with the PD group incidence being 23.2%, and the DP group incidence was 26.3%. Older age, High BMI, preop hyperglycemia, pre-op high HbA1c, pre-existing chronic pancreatitis, low remnant pancreatic volume and post-operative complications were associated with a high incidence of NODM.

Conclusions: The development of NODM after partial pancreatic resections for pancreatic adenocarcinoma is a severe complication that requires prompt diagnosis, careful monitoring and systematic management. Hence, healthcare professionals should have detailed knowledge of the surgical procedure and its potential for diabetes complications postoperatively, using risk factor assessment.

INTRODUCTION

Pancreatic cancer is among the deadliest types of cancer, characterized by its insidious onset, aggressive behavior, with poor outcomes. According to estimates from GLOBOCAN 2020, pancreatic cancer continues to contribute significantly to the global disease burden, ranking as the 12th most prevalent cancer (2.6% of all cancers) and the 7th leading cause of cancer-related deaths (4.7% of all cancers) [1]. Pancreatic adenocarcinoma constitutes 90% of all known pancreatic cancer cases [2].

The management of Pancreatic Adenocarcinoma include various options such as surgery, chemotherapy, radiotherapy and newer molecular therapies such as targeted therapy, immunotherapy etc. Nevertheless, the primary treatment approach continues to be surgical resection and include procedures such as Pancreaticoduodenectomy (PD) also known as the Whipple procedure, distal pancreatectomy (DP) which involves the tail or tail and a portion of the body, central pancreatectomy (CP), and total pancreatectomy (TP) [3, 4].

With rapid progress in imaging technology, it has enabled earlier identification and removal of pancreatic tumors [5]. As a result of diagnosing lesions at a stage suitable for surgery sooner, the frequency of pancreatic surgical procedures has also risen [5, 6]. The survival rates following pancreatectomy for cancer have improved, probably due to earlier cancer detection, advancements in surgical methods, the concentration of pancreatic surgeries in high-volume hospitals, and with ready adoption of new chemotherapy drugs [7, 8].

A retrospective analysis of 959 patients who had pancreatic adenocarcinoma resection indicated survival rates of 19% at 5 years and 10% at 10 years following the surgery [9]. Consequently, the decline in both endocrine and exocrine functions can significantly affect the quality of life for the growing population of patients following pancreatectomy. Therefore, it is essential to prioritize the preservation of endocrine and exocrine functions during pancreatectomy [10].

New-onset diabetes mellitus (NODM) in patients without diabetes following surgery was classified based on the diagnostic criteria set by the American Diabetes Association (ADA), namely: (a) an HbA1c level of ≥6.5 %, (b) a fasting plasma glucose level of ≥126 mg/dl after at least 8 hours of fasting, or (c) a 2-hour plasma glucose level of ≥200 mg/dl during an oral glucose tolerance test [11]. NODM was defined as diagnosis of DM within two years of diagnosis of pancreatic carcinoma [12]. Pancreatic resection is a recognized cause of NODM, due to loss of islet mass [13].

Regarding post-pancreatectomy diabetes, the extent of endocrine insufficiency may be associated with the specific area of the pancreas that was removed, with distal pancreatectomy thought to have a greater likelihood of leading to glucagon deficiency and hypoglycemia because of the differences in islet cell distribution, predominantly located in the pancreatic body and tail [14, 15].

Regarding pancreaticoduodenectomy procedure, surgical removal of the pylorus and/or duodenum is expected to influence the action of incretins and the regulation of blood sugar. Studies indicate that these individuals exhibit heightened secretion of GLP-1, lowered levels of GIP, and decreased insulin secretion [16].

Multiple complications have been reported following the resection of different quantities of pancreatic tissue. Among these complications, endocrine insufficiency, including new-onset diabetes mellitus (NODM), is particularly challenging as it is closely linked to the prognosis of pancreatic cancer [17].

Since NODM can place a significant strain on patients, their families, and healthcare resources, it is crucial to determine how often NODM occurs and its severity, as well as to understand how diabetes impacts patients’ quality of life and overall lifespan.

Hence, to address these issues, we are conducting a systematic review to determine the incidence as well as risk factors associated with NODM in pancreatic adenocarcinoma, post resection.

RESULTS

Literature search

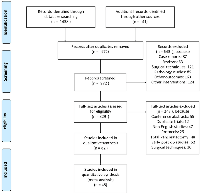

Out of the 1479 articles searched, 972 articles remained in the dataset after eliminating duplicates. We excluded 643 records that focused on individual case reports, reviews, specific tumor types, surgical methods, various postoperative complications, and studies on non-malignant and benign lesions. The full texts of 329 articles were reviewed, and 247 of these were discarded due to reasons such as being conference abstracts, duplicate studies, non-English publications, study protocols, research on total pancreatectomy, lacking information on long-term postoperative complications, or detailing surgical methods.

82 remaining articles were eligible, out of which 15 were eliminated because they either failed to report the patients’ preoperative diabetes status or had an inadequate number of participants. Additionally, 22 studies were omitted from the final evaluation due to poor quality or insufficient patient numbers regarding the study outcome. In the end, 45 studies involving pancreatic cancer patients who underwent either PD or DP were included in the quantitative analysis (Figure 1).

Study characteristics and quality assessment

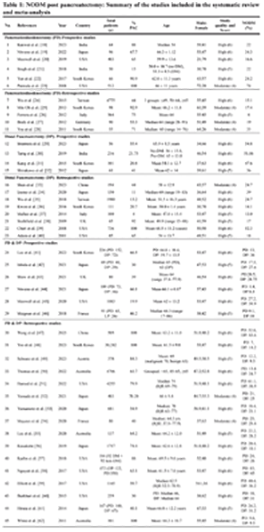

45 quantitative studies were chosen for this review (Table 1). Out of these 45 cohort studies, 11 studies included Pancreaticoduodenectomy (PD) alone, with 6 of them being prospective studies, while the remaining 5 studies were retrospective. 12 studies included Distal Pancreatectomy (DP) alone, with 4 of them being prospective studies, while the remaining 8 studies were retrospective. The remaining 22 studies included both PD and DP procedures, with 6 of them being prospective studies, while the remaining 16 studies were retrospective.

Out of the 45 cohort studies, the majority (n = 37) of studies had high quality, with eight (n = 08) studies having moderate quality critical appraisal scores, added in the Supplementary File 1 (Table).

Incidence of NODM

Among the 45 included studies, the overall incidence of NODM in the studied population was 24.5%. Incidence rates calculated using the random-effects model, concurred with our study findings, the forest plots of which were included in the Supplementary File 2.

We further divided the studies into 2 subgroups according to the type of resection (PD or DP) done for pancreatic cancer cases. For patients who underwent PD, the incidence of NODM was 23.2%, and for DP resection cases, the NODM incidence was 26.3%.

Analysis of risk factors for incidence of NODM

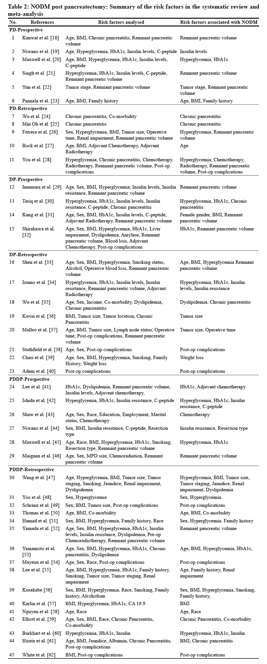

Around 37 risk factors were analysed in the 45 included studies, out of which 24 risk factors were associated with the incidence of NODM (Tables 2 and 3).

Sociodemographic factors

Based on the narrative synthesis of risk factors associated with NODM incidence, patient age is one of the important demographic variables associated with NODM incidence. Seven (07) studies showed that older age is associated with a high incidence of NODM, compared to the younger population, which may be due to decreased β-cell regenerative capacity, higher baseline insulin resistance and high post-operative complications [23, 27, 33, 50, 53, 55, 58].

The reported gender associated high incidence of NODM varied among the studies. While three (03) studies showed a higher incidence of NODM in male patients [48, 51, 55], one study observed higher NODM incidence in female patients, possibly due to hormonal influences on insulin sensitivity [31].

Three (03) studies showed a higher NODM incidence among patients with a family history of diabetes or pancreatic cancer. A positive family history of diabetes implies a genetic predisposition to β-cell dysfunction, insulin resistance, or both. Pancreatectomy may unmask latent glucose intolerance in genetically susceptible individuals [23, 55, 56].

One included study showed the association between race and NODM incidence, which showed a higher incidence in Asian populations. Asians had higher insulin sensitivity, but lower insulin secretion reserve compared to Caucasians, leading to higher NODM risk with minimal resection [58].

Lifestyle based factors

High pre-op BMI was associated with high NODM incidence in eight (08) studies, possibly due to increased insulin resistance, lipotoxicity and inflammation-induced β-cell dysfunction, increased ectopic fat deposition in the pancreas, exacerbating islet stress [23, 31, 33, 47, 50, 53, 56, 61].

Pre-op hyperglycemia was associated with high NODM incidence in fourteen (14) studies, implying it as one of the most important risk factors in NODM occurrence. It may be due to latent β-cell dysfunction, underlying insulin resistance, and paraneoplastic endocrine abnormalities related to pancreatic cancer [20, 26, 28, 30, 33, 34, 42, 45, 47, 48, 51, 53, 56, 60].

Elevated HbA1c was associated with high NODM incidence in nine (09) studies, as elevated HbA1c reflected subclinical glucose dysregulation or latent diabetes, making the endocrine pancreas more vulnerable post-resection [20, 30, 32, 34, 41, 42, 45, 53, 60].

One included study associated NODM incidence with weight loss, possibly due to cancer cachexia, which leads to systemic inflammation, proteolysis, and energy imbalance, which can impair insulin signalling. Weight loss >10% 21 is linked with loss of muscle mass, including pancreatic parenchymal atrophy and reduced β-cell mass [39].

One included study showed the association between smoking and NODM incidence, as smoking is associated with β-cell dysfunction, increased insulin resistance, and chronic pancreatic inflammation [56].

Insulin related factors

Three (03) included studies showed the association between pre-op insulin levels and NODM incidence. It may be due to low fasting insulin levels that may reflect impaired β-cell function before surgery. Postpancreatectomy, reduced pancreatic tissue may exacerbate β-cell loss, tipping borderline patients into diabetes [19, 34, 60].

Three (03) included studies showed the association between insulin resistance and NODM incidence. It may be due to insulin resistance burdens β-cells to overproduce insulin. After partial pancreatectomy, the diminished β-cell mass may be inadequate to maintain normoglycemia in insulin-resistant individuals. Tools such as HOMA-IR (Homeostasis Model Assessment-Insulin Resistance) are commonly used to quantify insulin resistance [34, 42, 44].

One included study showed the association between C-peptide levels and NODM incidence, as low C-peptide levels indicate depleted insulin-producing capacity [42].

Chronic pancreatitis (CP)

Six (06) studies showed the association between pre-existing chronic pancreatitis and NODM incidence in pancreatic cancer patients. Due to fibrosis and inflammation, Islet cell destruction occurs, resulting in impaired insulin secretion. With glucagon and pancreatic polypeptide deficiency, worsening glucose regulation occurs. CP patients often already exhibit subclinical glucose intolerance, which is unmasked or worsened postoperatively. When the surgery further reduces the remnant pancreatic volume, it pushes marginal islet cell function past a critical threshold, precipitating NODM [24, 25, 30, 35, 59, 61].

Tumor related factors

Three (03) included studies showed the association between tumor size and NODM incidence. Larger tumors are more likely to cause destruction of islet cells, ductal obstruction, and paraneoplastic insulin resistance. Bigger tumors often require more extensive resections, thus reducing functional endocrine tissue [36, 37, 47].

Tumor location determines the type of resection. Pancreaticoduodenectomy (Whipple’s) is indicated for pancreatic head tumors, which preserves more of the body and tail (endocrine-rich areas). Distal pancreatectomy is indicated for body/tail tumors, which removes islet-rich regions, as islet cell distribution is denser in the tail and body of the pancreas [19].

One included study showed the association between tumor stage and NODM incidence, as advanced tumor stage often reflects a more systemic inflammation, greater likelihood of pre-existing metabolic stress and requires extensive resection [22].

Biochemical risk factors

Two (02) included studies showed the association between dyslipidemia and NODM incidence. Elevated triglycerides and low HDL are features of the metabolic syndrome, which includes insulin resistance—a predictor of poor glycemic adaptation after pancreatic resection. The inflammatory milieu associated with dyslipidemia may further worsen post-surgical glucose control [35, 47].

One included study showed the association between deranged liver parameters and NODM incidence, possibly due to liver inflammation and steatosis promoting peripheral insulin resistance [47].

Two (02) included studies showed the association between impaired renal function and NODM incidence. Chronic kidney disease (CKD) results in insulin resistance, decreased insulin clearance, and inflammatory cytokine release [47, 55].

Operative and post-operative factors

One included study showed the association between operative factors, such as prolonged operative time and heavy blood loss, with NODM incidence. Pronged operative times may be due to complex surgical procedures, which lead to stress hyperglycemia, prolonged anesthesia effects on glucose metabolism, and tissue ischemia-reperfusion injury. Heavy blood loss leads to hemodynamic instability, hypoperfusion of the pancreatic remnant, systemic inflammatory response affecting islet cells, and insulin sensitivity [37].

Post-operative complications were associated with high NODM incidence in six (06) studies. Postoperative pancreatic fistula (POPF) and local inflammation can cause injury to islet cells in the pancreatic remnant, reducing insulin secretion. Systemic infections and sepsis induce insulin resistance via cytokine release. Delayed gastric emptying and nutritional deficits may impair glucose metabolism and insulin sensitivity. Prolonged hospitalization and recurrent complications exacerbate metabolic stress [28, 38, 40, 49, 54, 62].

Remnant pancreatic volume

Remnant pancreatic volume was associated with high NODM incidence in eleven (11) studies, implying it as one of the most important risk factors in NODM occurrence. Partial pancreatectomy further reduces the remnant pancreatic volume, pushing marginal islet cell function past a critical threshold, precipitating NODM [18, 21, 22, 26, 28, 29, 31, 32, 33, 46, 52].

Co-morbidity

Two (02) included studies showed the association between pre-op co-morbidity and NODM incidence. High Charlson co-morbidity index (CCI) scores are associated with impaired glucose homeostasis, increased baseline insulin resistance (e.g., due to obesity, cardiovascular disease, CKD). These factors can amplify the glycemic impact of pancreatectomy, especially in major resections [50, 59].

Chemotherapy

Three (03) studies showed the association between chemotherapy and NODM incidence. Some chemotherapy agents cause direct pancreatic toxicity, while some other agents may damage pancreatic islet cells, impairing insulin secretion. Chemotherapy induces systemic inflammation with cytokine release, promoting insulin resistance. Chemotherapy-associated anorexia and malabsorption affect glucose homeostasis. Chemotherapeutic drugs may also interfere with insulin receptor signaling [28, 41, 43].

Radiotherapy

One included study showed the association between radiotherapy and NODM incidence. Radiotherapy may cause direct islet cell damage, which may reduce insulin secretion. Fibrosis and vascular injury in the pancreatic remnant impair blood supply and endocrine function. The inflammatory response triggered by radiation may promote insulin resistance [28].

The forest plot of the associated risk factors with the strongest weight of evidence was done and included in the Supplementary File 2.

DISCUSSION

To the best of our understanding, this is the first systematic review examining the incidence of NODM and its related risk factors specifically in patients with Pancreatic Adenocarcinoma (PAC) who have undergone partial pancreatectomy. Our analysis incorporated research from both developed and developing countries, comprising a total of 45 studies.

Among the patients in this systematic review who underwent partial pancreatectomy for pancreatic adenocarcinoma, the overall incidence of NODM in the studied population was 24.5%, affecting up to one-fourth of the study population. In the 2 subgroups according to the type of resection (PD or DP) done for pancreatic cancer cases, patients who underwent PD, the incidence of NODM was 23.2%, and for DP resection cases, the NODM incidence was 26.3%.

The occurrence of NODM has been evaluated concerning various types of pancreatic surgeries in prior studies. Multiple clinical studies produced inconsistent outcomes. While some researchers suggested that patients undergoing DP faced an increased risk of developing NODM, other studies indicated a marginally higher incidence of NODM in patients who had DP compared to those who underwent PD, yet this difference was not statistically significant [46, 63]. Our review mirrored these findings, revealing that the incidence of NODM after DP (26.3%) was slightly above that of PD (23.2%).

A systematic review and meta-analysis were undertaken by Beger et al, in post PD resections for both benign and malignant tumors, which included quantitative assessments from 19 studies. They found that the cumulative incidence of NODM was 14.5% for the group with benign tumors, 15.5% for the group with malignant tumors, and 22.2% for the combined group of both benign and malignant tumors [64].

A similar systematic review and Meta-analysis were undertaken by De Bruijn et al, in exclusively post DP groups for pancreatic disorders involving quantitative analysis of 26 studies. This review indicates that the average cumulative incidence of NODM) following DP procedures conducted for benign or potentially malignant conditions is 14% [65]. But a recent study by Yu et al., who did a systematic review and Meta-analysis of NODM after DP for pancreatic disorders involving quantitative analysis of 18 studies. The rate of NODM was 23% in patients with pancreatic tumors. However, the study included both benign and malignant lesions [66]. Our study included only malignant pancreatic adenocarcinoma cases and showed slightly higher NODM incidence for both PD and DP types.

Regarding the risk factors associated with NODM incidence in this group of patients, we did a narrative synthesis of up to 37 different variables related to NODM incidence. Out of all these variables, older age, high BMI, pre-op hyperglycemia, pre-op high HbA1c, pre-existing chronic pancreatitis, poor remnant pancreatic volume, and severe post-operative complications were associated with NODM incidence.

These results were consistent with those previously published studies and reviews.

Older patients undergoing pancreatectomy for PAC were associated with high NODM incidence. A similar finding was observed in a study, which showed that age >60 years was an independent risk factor for NODM after pancreaticoduodenectomy [67]. Regarding gender, the results were mixed. Some studies suggest females were more susceptible, possibly due to hormonal influences on insulin sensitivity [31]. Some included studies suggest where males are more likely to develop chronic pancreatitis and thus more prone to developing DM [68]. Others find no significant difference in relation to gender, after adjusting for BMI and age [69].

Regarding race and ethnicity as influencers of NODM risk, our analysis showed a higher incidence in Asian populations [58], which was similar to reported findings by a study that indicated that being from a non-White race or ethnicity was independently linked to poorer outcomes following pancreatic cancer surgery [70]. Another study observed that a higher baseline prevalence of pre-diabetes and NODM in the Indian cohort compared to Western reports [71]. Regarding the Family history of diabetes, as an influencer of NODM risk, our analysis showed higher NODM incidence in this population. One study reflected the similar findings, which observed that Family history of diabetes emerged as a significant non-modifiable risk factor, especially in patients without pre-existing hyperglycemia [72].

Our analysis showed that high BMI was associated with NODM incidence in this population. A study concurred with our findings, which showed that high BMI had both poorer glycemic profiles and a greater tendency to develop NODM after surgery [73].

Our analysis showed that Pre-op hyperglycemia and high HbA1c were among the most important risk factors associated with NODM incidence. Similar findings were observed in a study that showed that Preoperative impaired fasting glucose and mildly elevated HbA1c predicted postoperative diabetes [74]. Another study showed that patients with elevated preoperative HbA1c had a significantly higher risk of developing NODM postoperatively [75].

In our analysis, pre-existing chronic pancreatitis as a risk factor was associated with NODM incidence.

One study showed similar findings that patients with pre-existing CP had significantly lower insulin and C-peptide levels of post-surgery, predisposing them to NODM [76]. Another study showed that Chronic inflammation and fibrosis reduce the functional β-cell mass, making patients prone to NODM post pancreatectomy [77]. Another study indicates that it is conceivable that chronic pancreatitis may affect the likelihood of developing NODM [15].

Regarding the tumor size, as an influencer of NODM risk, our analysis showed higher NODM incidence in this population. One study showed similar findings that a tumor size was independently associated with increased NODM incidence post-resection in localized disease [78].

Our analysis showed that remnant pancreatic volume was one of the most important risk factors associated with NODM incidence. One recent study showed similar findings that reduced remnant pancreatic volume, causing beta-cell dysfunction, might be one of the mechanisms of NODM secondary to PAC [79]. A different study noted that it is likely that the volume and health of remaining pancreatic tissue may affect the likelihood of developing new-onset diabetes mellitus [15].

Our analysis showed that a high incidence of post-operative complications was associated with NODM incidence. Few studies showed similar findings that patients with clinically relevant postoperative pancreatic fistula had a significantly higher incidence of NODM at 6 months post-pancreatectomy [80, 81]. Another study showed that patients with delayed gastric emptying had impaired glycemic control at 3 and 6 months postoperatively [82].

Limitations

It is important to acknowledge that this review has certain limitations and should be interpreted accordingly. To begin with, since the review was limited to works published in English, there is a possibility that relevant studies in other languages may have been missed. Secondly, variations in surgical methods, such as the amount of pancreas removed during routine clinical practices, can differ significantly between institutions, surgeons, and patients, along with surgical techniques like laparotomy or laparoscopy, and whether the spleen was preserved, leading to substantial heterogeneity in the surgical approaches. Third, studies employed different methods for reporting the incidence of NODM, which lacked standardization concerning follow-up periods. Fourth, the risk stratification for pre-existing pancreatic conditions could not be thoroughly clarified, nor were confounding factors adequately addressed, as this was based on the original designs and reports of the studies included. Fifth, potential for publication bias, as smaller studies or those reporting null associations between surgical or metabolic factors and NODM may be underrepresented in the literature. This selective reporting can overestimate pooled incidence or effect sizes, thereby limiting the generalizability and external validity of the analysis.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

We submitted our review protocol and registered with PROSPERO (CRD420251024206) and followed the established protocol for systematic reviews as per PRISMA statement [83].

Search strategy

We conducted searches in the databases MEDLINE, Cochrane, Embase, and Scopus to identify relevant studies, following the guidelines outlined in the Peer Review of Electronic Search Strategies (PRESS) [84]. The PubMed database was queried using medical subject headings (MeSH). Search terms included “Pancreatic carcinoma,” “Pancreatectomy,” and “Diabetes mellitus.” Our search strategy was broad to ensure a comprehensive review of the available literature and to capture all pertinent evidence. We also refined our search strategy by closely reviewing the references of the articles we gathered. Our search was confined to English-language publications published from January 2000 to March 2025 (Supplementary File 3).

Eligibility criteria and study selection

The research selection process involved two reviewers (KAK & AKR). All studies that provided information on postoperative pancreatic endocrine function in patients with pancreatic adenocarcinoma (PAC) who had either a Pancreaticoduodenectomy (PD) or Distal Pancreatectomy (DP) were considered in the initial evaluation. Studies that (1) did not report the incidence of preoperative diabetes, (2) concentrated on surgical techniques, and (3) had a follow-up period of less than 3 months were excluded from the analysis.

Data extraction and quality assessment

Data extraction

Two investigators (KAK & AKR) conducted a separate screening of the titles, abstracts, and full articles. The extracted data included the patients’ gender, average age, existence of preoperative diabetes; occurrence of postoperative diabetes; incidence of new onset diabetes mellitus (NODM), the type of pancreatectomy performed (PD or DP), as well as the criteria used to diagnose diabetes, which included fasting blood glucose (FBG), glycated hemoglobin (HbA1c) levels, or an oral glucose tolerance test (OGTT); and the duration of the follow-up period.

A narrative synthesis outlines the risk factors linked to the onset of NODM in these patient populations, providing an analysis by subgroups in relation to PD versus DP groups.

Quality assessment

Quality assessments were conducted to assess the robustness and caliber of the evidence produced by the studies. The Newcastle–Ottawa scale (NOS) was utilized to evaluate all cohort studies, with a NOS score of 6 or higher indicating a study of high quality [85].

Statistical analyses

The overall incidence of NODM was determined using the incidence rate method. When the publication did not provide the NODM rate, it was computed by dividing the number of patients with NODM by the number of patients who did not have preoperative diabetes. Subgroup analyses were conducted on the groups of patients with surgical procedures of PD vs. DP. A narrative synthesis was performed to assess the associated risk factors.

CONCLUSIONS

This systematic review aims to remind surgeons that a deficiency in pancreatic endocrine function is a significant long-term complication following pancreatectomy. Older age, high BMI, pre-op hyperglycemia, pre-op high HbA1c, pre-existing chronic pancreatitis, poor remnant pancreatic volume, and severe post-operative complications were associated with NODM incidence. Larger cohort studies with more extensive patient populations should be carried out to better understand the risk factors linked to NODM following pancreatectomy. It is essential to implement suitable screening and enhance patient education for individuals with recognized risk factors.

Abbreviations

PAC: Pancreatic Adenocarcinoma; NODM: New-Onset Diabetes Mellitus; PD: Pancreaticoduodenectomy; DP: Distal Pancreatectomy; TP: Total Pancreatectomy; BMI: Body Mass Index; OGTT: Oral Glucose Tolerance Test; HbA1c: Glycated Hemoglobin; CP: Chronic Pancreatitis; POPF: Postoperative Pancreatic Fistula; BMI: Body Mass Index.

AUTHOR CONTRIBUTIONS

KAK developed the initial concept idea, created, and formulated the systematic review protocol. The search strategies were designed by KAK, AKR, KSB, and KSAR. KAK, YA, CR, KM, and KND conducted the searches and obtained articles. The study selection, data extraction, and quality assessment were carried out by KAK, VSB, and KM. KAK prepared the first draft of the manuscript. All authors contributed by discussing, advising, and revising the manuscript. Every author reviewed and approved the final version.

CONFLICTS OF INTEREST

Authors have no conflicts of interest to declare.

ETHICAL STATEMENT

This review utilized exclusively data that has been previously published. We did not have direct access to the primary data from the studies that were incorporated into the review. Consequently, ethical approval was not required.

FUNDING

No funding was used for this paper.

- 1. Global Cancer Statistics 2020: GLOBOCAN Estimates of Incidence and Mortality Worldwide for 36 Cancers in 185 Countries. CA Cancer J Clin. 2021; 71:209–49. https://doi.org/10.3322/caac.21660. PMID:33538338

- 2. Pancreatic ductal adenocarcinoma: risk factors, screening, and early detection. World J Gastroenterol. 2014; 20:11182–98. https://doi.org/10.3748/wjg.v20.i32.11182. PMID:25170203

- 3. Diabetes mellitus and pancreatic cancer in a population-based case-control study in the San Francisco Bay Area, California. Cancer Epidemiol Biomarkers Prev. 2006; 15:1458–63. https://doi.org/10.1158/1055-9965.EPI-06-0188. PMID:16896032

- 4. Long-term survival after curative resection for pancreatic ductal adenocarcinoma. Clinicopathologic analysis of 5-year survivors. Ann Surg. 1996; 223:273–79. https://doi.org/10.1097/00000658-199603000-00007. PMID:8604907

- 5. Pancreatic incidentalomas: high rate of potentially malignant tumors. J Am Coll Surg. 2009; 209:313–19. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jamcollsurg.2009.05.009. PMID:19717035

- 6. Improving outcome for patients with pancreatic cancer through centralization. Br J Surg. 2011; 98:1455–62. https://doi.org/10.1002/bjs.7581. PMID:21717423

- 7. Pancreatic surgery. Curr Opin Gastroenterol. 2013; 29:552–58. https://doi.org/10.1097/MOG.0b013e3283639359. PMID:23892537

- 8. Patient selection and the volume effect in pancreatic surgery: unequal benefits? HPB (Oxford). 2014; 16:899–906. https://doi.org/10.1111/hpb.12283. PMID:24905343

- 9. Pancreatic ductal adenocarcinoma: long-term survival does not equal cure. Surgery. 2012 (Suppl 1); 152:S43–49. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.surg.2012.05.020. PMID:22763261

- 10. Risk factors for development of diabetes mellitus (Type 3c) after partial pancreatectomy: A systematic review. Clin Endocrinol (Oxf). 2020; 92:396–406. https://doi.org/10.1111/cen.14168. PMID:32017157

- 11. 2. Diagnosis and Classification of Diabetes: Standards of Care in Diabetes-2024. Diabetes Care. 2024 (Suppl 1); 47:S20–42. https://doi.org/10.2337/dc24-S002. PMID:38078589

- 12. Diverse transitions in diabetes status during the clinical course of patients with resectable pancreatic cancer. Jpn J Clin Oncol. 2020; 50:1403–11. https://doi.org/10.1093/jjco/hyaa136. PMID:32761096

- 13. Resectability of presymptomatic pancreatic cancer and its relationship to onset of diabetes: a retrospective review of CT scans and fasting glucose values prior to diagnosis. Am J Gastroenterol. 2007; 102:2157–63. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1572-0241.2007.01480.x. PMID:17897335

- 14. Impaired glucose-induced glucagon suppression after partial pancreatectomy. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2009; 94:2857–63. https://doi.org/10.1210/jc.2009-0826. PMID:19491219

- 15. Impact of glucagon response on postprandial hyperglycemia in men with impaired glucose tolerance and type 2 diabetes mellitus. Metabolism. 2005; 54:1168–73. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.metabol.2005.03.024. PMID:16125528

- 16. Removal of duodenum elicits GLP-1 secretion. Diabetes Care. 2013; 36:1641–46. https://doi.org/10.2337/dc12-0811. PMID:23393218

- 17. Postoperative mortality in cancer patients with preexisting diabetes: systematic review and meta-analysis. Diabetes Care. 2010; 33:931–39. https://doi.org/10.2337/dc09-1721. PMID:20351229

- 18. Pancreatic Dysfunction and Reduction in Quality of Life Is Common After Pancreaticoduodenectomy. Dig Dis Sci. 2023; 68:3167–73. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10620-023-07966-6. PMID:37160540

- 19. Three-Year Observation of Glucose Metabolism After Pancreaticoduodenectomy: A Single-Center Prospective Study in Japan. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2022; 107:3362–69. https://doi.org/10.1210/clinem/dgac529. PMID:36074913

- 20. Development of Diabetes after Pancreaticoduodenectomy: Results of a 10-Year Series Using Prospective Endocrine Evaluation. J Am Coll Surg. 2019; 228:400–12.e2. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jamcollsurg.2018.12.042. PMID:30690075

- 21. Diabetes after pancreaticoduodenectomy: can we predict it? J Surg Res. 2018; 227:211–19. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jss.2018.02.010. PMID:29804855

- 22. Does the pancreatic volume reduction rate using serial computed tomographic volumetry predict new onset diabetes after pancreaticoduodenectomy? Medicine (Baltimore). 2017; 96:e6491. https://doi.org/10.1097/MD.0000000000006491. PMID:28353594

- 23. Prevalence and clinical profile of pancreatic cancer-associated diabetes mellitus. Gastroenterology. 2008; 134:981–87. https://doi.org/10.1053/j.gastro.2008.01.039. PMID:18395079

- 24. Glycemic Change After Pancreaticoduodenectomy: A Population-Based Study. Medicine (Baltimore). 2015; 94:e1109. https://doi.org/10.1097/MD.0000000000001109. PMID:26166104

- 25. Risk factors for pancreatogenic diabetes after pancreaticoduodenectomy. Korean J Hepatobiliary Pancreat Surg. 2012; 16:167–71. https://doi.org/10.14701/kjhbps.2012.16.4.167. PMID:26388929

- 26. Immediate post-resection diabetes mellitus after pancreaticoduodenectomy: incidence and risk factors. HPB (Oxford). 2013; 15:170–74. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1477-2574.2012.00520.x. PMID:23374356

- 27. Late complications after pancreaticoduodenectomy with pancreaticogastrostomy. J Gastrointest Surg. 2012; 16:914–19. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11605-011-1805-2. PMID:22374385

- 28. Long-term effects of pancreaticoduodenectomy on glucose metabolism. ANZ J Surg. 2012; 82:447–51. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1445-2197.2012.06080.x. PMID:22571457

- 29. High Incidence of Diabetes Mellitus After Distal Pancreatectomy and Its Predictors: A Long-term Follow-up Study. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2024; 109:619–30. https://doi.org/10.1210/clinem/dgad634. PMID:37889837

- 30. Diabetes development after distal pancreatectomy: results of a 10-year series. HPB (Oxford). 2020; 22:1034–41. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.hpb.2019.10.2440. PMID:31718897

- 31. Endocrine Function Impairment After Distal Pancreatectomy: Incidence and Related Factors. World J Surg. 2016; 40:440–46. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00268-015-3228-9. PMID:26330237

- 32. Pancreatic volumetric assessment as a predictor of new-onset diabetes following distal pancreatectomy. J Gastrointest Surg. 2012; 16:2212–19. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11605-012-2039-7. PMID:23054900

- 33. Clinical utility of resected pancreatic volume ratio calculation for predicting postoperative new-onset diabetes mellitus after distal pancreatectomy-a propensity-matched analysis. Heliyon. 2023; 9:e15998. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.heliyon.2023.e15998. PMID:37206003

- 34. Evaluation of allowable pancreatic resection rate depending on preoperative risk factors for new-onset diabetes mellitus after distal pancreatectomy. Pancreatology. 2020; 20:1526–33. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.pan.2020.08.005. PMID:32855059

- 35. Changes in glucose metabolism after distal pancreatectomy: a nationwide database study. Oncotarget. 2018; 9:11100–108. https://doi.org/10.18632/oncotarget.24325. PMID:29541399

- 36. An Analysis of Complications, Quality of Life, and Nutritional Index After Laparoscopic Distal Pancreatectomy with Regard to Spleen Preservation. J Laparoendosc Adv Surg Tech A. 2016; 26:335–42. https://doi.org/10.1089/lap.2015.0171. PMID:26982249

- 37. Laparoscopic distal pancreatectomy: analysis of trends in surgical techniques, patient selection, and outcomes. Surg Endosc. 2015; 29:1952–62. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00464-014-3890-2. PMID:25303912

- 38. Distal pancreatectomy: what is the standard for laparoscopic surgery? HPB (Oxford). 2009; 11:210–14. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1477-2574.2009.00008.x. PMID:19590649

- 39. Pancreatic cancer-associated diabetes mellitus: prevalence and temporal association with diagnosis of cancer. Gastroenterology. 2008; 134:95–101. https://doi.org/10.1053/j.gastro.2007.10.040. PMID:18061176

- 40. Distale Pankreasresektion--Indikation, Verfahren, postoperative Ergebnisse [Distal pancreatic resection--indications, techniques and complications]. Zentralbl Chir. 2001; 126:908–12. https://doi.org/10.1055/s-2001-19149. PMID:11753802

- 41. Glucose Regulation after Partial Pancreatectomy: A Comparison of Pancreaticoduodenectomy and Distal Pancreatectomy in the Short and Long Term. Diabetes Metab J. 2023; 47:703–14. https://doi.org/10.4093/dmj.2022.0205. PMID:37349082

- 42. Glucose Tolerance after Pancreatectomy: A Prospective Observational Follow-Up Study of Pancreaticoduodenectomy and Distal Pancreatectomy. J Am Coll Surg. 2021; 233:753–62. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jamcollsurg.2021.08.688. PMID:34530126

- 43. Long term quality of life amongst pancreatectomy patients with diabetes mellitus. Pancreatology. 2021; 21:501–508. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.pan.2021.01.012. PMID:33509685

- 44. Glucose Metabolism After Pancreatectomy: Opposite Extremes Between Pancreaticoduodenectomy and Distal Pancreatectomy. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2021; 106:e2203–14. https://doi.org/10.1210/clinem/dgab036. PMID:33484558

- 45. Post-Pancreatectomy Diabetes Index: A Validated Score Predicting Diabetes Development after Major Pancreatectomy. J Am Coll Surg. 2020; 230:393–402.e3. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jamcollsurg.2019.12.016. PMID:31981618

- 46. Risk factors of exocrine and endocrine pancreatic insufficiency after pancreatic resection: A multi-center prospective study. J Visc Surg. 2018; 155:173–81. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jviscsurg.2017.10.007. PMID:29396112

- 47. Predictive value of perioperative fasting blood glucose for post pancreatectomy diabetes mellitus in pancreatic ductal carcinoma patients. World J Surg Oncol. 2025; 23:55. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12957-025-03705-5. PMID:39955538

- 48. Risk of Ischemic Heart Disease in Patients With Postpancreatectomy Diabetes and Pancreatic Cancer: A Population-Based Study. J Am Heart Assoc. 2023; 12:e031321. https://doi.org/10.1161/JAHA.123.031321. PMID:38084734

- 49. Incidence of Diabetes Mellitus and Its Impact on Outcomes in Patients Undergoing Surgical Pancreatectomy for Non-Malignant and Malignant Pancreatobiliary Diseases-A Retrospective Analysis. J Clin Med. 2023; 12:7532. https://doi.org/10.3390/jcm12247532. PMID:38137600

- 50. Prevalence and Risk Factors for Pancreatic Insufficiency After Partial Pancreatectomy. J Gastrointest Surg. 2022; 26:1425–35. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11605-022-05302-3. PMID:35318597

- 51. Pancreatogenic Diabetes after Partial Pancreatectomy: A Common and Understudied Cause of Morbidity. J Am Coll Surg. 2022; 235:838–45. https://doi.org/10.1097/XCS.0000000000000360. PMID:36102556

- 52. Investigation of the influence of pancreatic surgery on new-onset and persistent diabetes mellitus. Ann Gastroenterol Surg. 2021; 5:575–84. https://doi.org/10.1002/ags3.12435. PMID:34337306

- 53. Development of a preoperative prediction model for new-onset diabetes mellitus after partial pancreatectomy: A retrospective cohort study. Medicine (Baltimore). 2021; 100:e26311. https://doi.org/10.1097/MD.0000000000026311. PMID:34128870

- 54. Long-term health after pancreatic surgery: the view from 9.5 years. HPB (Oxford). 2021; 23:595–600. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.hpb.2020.08.017. PMID:32988751

- 55. Diabetes-related outcomes after pancreatic surgery. ANZ J Surg. 2020; 90:2004–10. https://doi.org/10.1111/ans.16129. PMID:32691521

- 56. Long-Term Endocrine and Exocrine Insufficiency After Pancreatectomy. J Gastrointest Surg. 2019; 23:1604–13. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11605-018-04084-x. PMID:30671791

- 57. Survival and glycemic control outcomes among patients with coexisting pancreatic cancer and diabetes mellitus. Future Sci OA. 2018; 4:FSO291. https://doi.org/10.4155/fsoa-2017-0144. PMID:29682326

- 58. Development of Postoperative Diabetes Mellitus in Patients Undergoing Distal Pancreatectomy versus Whipple Procedure. Am Surg. 2017; 83:1050–53. PMID:29391093

- 59. Population-Level Incidence and Predictors of Surgically Induced Diabetes and Exocrine Insufficiency after Partial Pancreatic Resection. Perm J. 2017; 21:16–95. https://doi.org/10.7812/TPP/16-095. PMID:28406793

- 60. Incidence and severity of pancreatogenic diabetes after pancreatic resection. J Gastrointest Surg. 2015; 19:217–25. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11605-014-2669-z. PMID:25316483

- 61. Predictive factors for change of diabetes mellitus status after pancreatectomy in preoperative diabetic and nondiabetic patients. J Gastrointest Surg. 2014; 18:1597–603. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11605-014-2521-5. PMID:25002020

- 62. Impact of pancreatic cancer and subsequent resection on glycemic control in diabetic and nondiabetic patients. Am Surg. 2011; 77:1032–37. PMID:21944519

- 63. Different incretin responses after pancreatoduodenectomy and distal pancreatectomy. Pancreas. 2012; 41:455–60. https://doi.org/10.1097/MPA.0b013e3182319d7c. PMID:22422137

- 64. New Onset of Diabetes and Pancreatic Exocrine Insufficiency After Pancreaticoduodenectomy for Benign and Malignant Tumors: A Systematic Review and Meta-analysis of Long-term Results. Ann Surg. 2018; 267:259–70. https://doi.org/10.1097/SLA.0000000000002422. PMID:28834847

- 65. New-onset diabetes after distal pancreatectomy: a systematic review. Ann Surg. 2015; 261:854–61. https://doi.org/10.1097/SLA.0000000000000819. PMID:24983994

- 66. New-Onset Diabetes Mellitus After Distal Pancreatectomy: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. J Laparoendosc Adv Surg Tech A. 2020; 30:1215–22. https://doi.org/10.1089/lap.2020.0090. PMID:32559393

- 67. Surgery for elderly patients with resectable pancreatic cancer, a comparison with non-surgical treatments: a retrospective study outcomes of resectable pancreatic cancer. BMC Cancer. 2019; 19:1090. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12885-019-6255-3. PMID:31718565

- 68. Male gender and increased body mass index independently predicts clinically relevant morbidity after spleen-preserving distal pancreatectomy. World J Gastrointest Surg. 2018; 10:84–89. https://doi.org/10.4240/wjgs.v10.i8.84. PMID:30510633

- 69. Rising BMI Is Associated with Increased Rate of Clinically Relevant Pancreatic Fistula after Distal Pancreatectomy for Pancreatic Adenocarcinoma. Am Surg. 2019; 85:1376–80. PMID:31908221

- 70. The impact of race/ethnicity on pancreaticoduodenectomy outcomes for pancreatic cancer. J Surg Oncol. 2023; 127:99–108. https://doi.org/10.1002/jso.27113. PMID:36177773

- 71. Evolution of pancreatoduodenectomy in a tertiary cancer center in India: improved results from service reconfiguration. Pancreatology. 2013; 13:63–71. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.pan.2012.11.302. PMID:23395572

- 72. Radiological and surgical implications of neoadjuvant treatment with FOLFIRINOX for locally advanced and borderline resectable pancreatic cancer. Ann Surg. 2015; 261:12–17. https://doi.org/10.1097/SLA.0000000000000867. PMID:25599322

- 73. Risk factors for new-onset diabetes mellitus after distal pancreatectomy. BMJ Open Diabetes Res Care. 2020; 8:e001778. https://doi.org/10.1136/bmjdrc-2020-001778. PMID:33122295

- 74. Residual total pancreatectomy: Short-and long-term outcomes. Pancreatology. 2016; 16:646–51. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.pan.2016.04.034. PMID:27189919

- 75. Effects of preoperative long-term glycemic control on operative outcomes following pancreaticoduodenectomy. Am J Surg. 2015; 209:1053–62. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.amjsurg.2014.06.029. PMID:25242683

- 76. Chronic pancreatitis. Nat Rev Dis Primers. 2017; 3:17060. https://doi.org/10.1038/nrdp.2017.60. PMID:28880010

- 77. Diabetes associated with pancreatic diseases. Curr Opin Gastroenterol. 2015; 31:400–6. https://doi.org/10.1097/MOG.0000000000000199. PMID:26125315

- 78. Relationship between tumour size and outcome in pancreatic ductal adenocarcinoma. Br J Surg. 2017; 104:600–7. https://doi.org/10.1002/bjs.10471. PMID:28177521

- 79. Remnant Pancreas Volume Affects New-Onset Impaired Glucose Homeostasis Secondary to Pancreatic Cancer. Biomedicines. 2024; 12:1653. https://doi.org/10.3390/biomedicines12081653. PMID:39200119

- 80. Incidence of clinically relevant postoperative pancreatic fistula in patients undergoing open and minimally invasive pancreatoduodenectomy: a population-based study. J Minim Invasive Surg. 2024; 27:95–108. https://doi.org/10.7602/jmis.2024.27.2.95. PMID:38887001

- 81. Predictors and Outcomes of Pancreatic Fistula Following Pancreaticoduodenectomy: a Dual Center Experience. Indian J Surg Oncol. 2021; 12:22–30. https://doi.org/10.1007/s13193-020-01195-3. PMID:33814828

- 82. Delayed gastric emptying is associated with increased risk of mortality in patients undergoing pancreaticoduodenectomy for pancreatic adenocarcinoma. Updates Surg. 2023; 75:523–30. https://doi.org/10.1007/s13304-022-01404-4. PMID:36309940

- 83. Preferred reporting items for systematic reviews and meta-analyses: the PRISMA Statement. Open Med. 2009; 3:e123–30. PMID:21603045

- 84. An evidence-based practice guideline for the peer review of electronic search strategies. J Clin Epidemiol. 2009; 62:944–52. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jclinepi.2008.10.012. PMID:19230612

- 85. The Newcastle-Ottawa Scale (NOS) for assessing the quality of nonrandomized studies in meta-analyses. https://www.ohri.ca/. 2021. http://www.ohri.ca/programs/clinical_epidemiology/oxford.asp.